In December 2024, we took our long-delayed trip to Kongo Central province and specifically Muanda, on DRC's coast. We'd previously planned to travel there in December 2022, but heavy rains washed away a portion of the N1/Route de Matadi (the main highway leading from Kinshasa to DRC's port in Matadi). Some repairs were made, but large sections of the road were one-way which would have made an already slow drive even longer.

|

| View of Matadi and the Congo River. |

After a night in Matadi we continued to Boma, the capital under King Leopold II's Congo Free State until 1923. We later learned from some other customers at the bar/historical sight Belvédère that it was not the first capital of the Congo Free State, and that Vivi across the river from Matadi held that status from July 1885-May 1886.

|

| Ship heading past Boma up the Congo River to Matadi. |

|

| The first cars in the Congo, they belonged to a German named Fischer. |

We then headed north to INERA Luki, and agriculture and forestry research station where a TASOK colleague of ours grew up. His brother continues to work there, and was a great help getting to and from Luki (i.e. finding a driver who was willing to take us the 6.5 kms offroad to reach INERA, then riding with us) and then when we had a family member fall sick and need medical treatment in Boma.

|

| Dimensions of Central Africa's biggest tree. |

Onwards to Muanda, which was just a 1-1.5 hour drive from Boma. Once you get past the port at Matadi and cross the river, traffic is much calmer thanks to the smaller amount of heavy goods trucks on the road. Besides increased traffic, the Matadi-Kinshasa also features numerous truck breakdowns (or trucks that veered into the deep gutter alongside the highway), which requires drivers to weave around them while on the lookout for oncoming traffic.

|

| Fishermen at Tonde beach, Muanda. |

In Muanda we stayed at a guesthouse on the grounds of a Catholic church, Maison d'accueil des Sœurs de la Charité. This was a couple of hundred meters from Plage Tonde, a pleasant enough beach with chairs and umbrellas available for the cost of a drink, with shrimp, fish and other food available on the grill. The sea was a bit rough, but the kids enjoyed riding the waves near shore, building in the sand, and, one time, helping fishermen pull in their net (they offered us a decent-sized fish for our efforts, despite a meager haul for what was a lot of effort on their part).

Per Christian at the ICCN outpost/hatchery, the turtles, Olive Ridleys, laid eggs in October and about five weeks later they hatch. So every day there were 1-2 batches of turtles hatching, so we went twice to help count them and release them onto the beach.

(Left: first church in Congo, brought prefabricated from Belgium. Right: oil derrick monument, Muanda.)

|

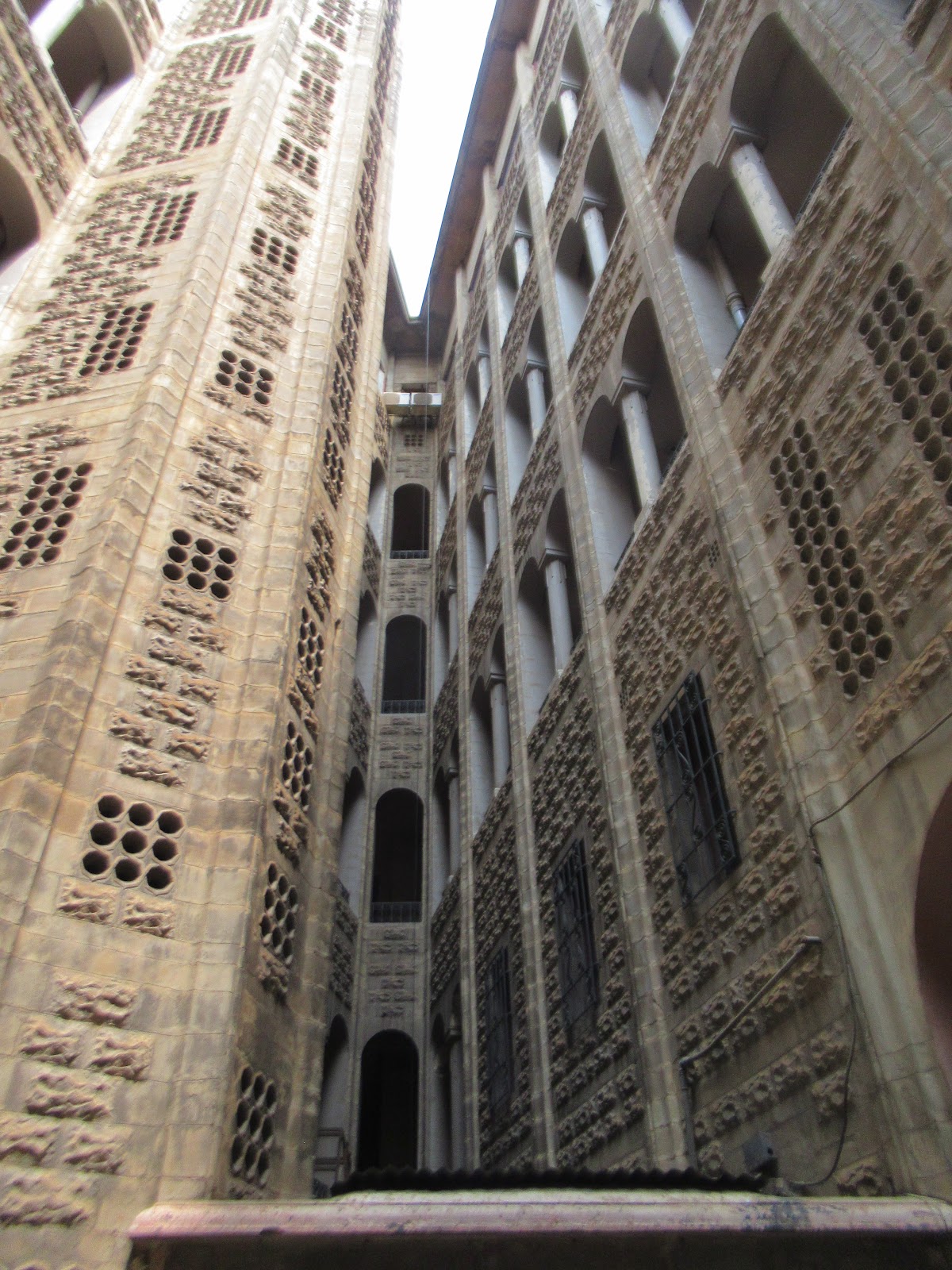

| Former Governor's residence, Boma. |

On our return trip through Matadi, we made a visit to Belvédère, sight of a hillside monument to the construction of the train from Matadi to Kinshasa (built to bypass the rapids on the Congo River). The main feature, a bronze topographical map mounted on marble, is mostly surrounded by a bar/restaurant, although it was covered in a tarp to protect it from the rain.

|

| "Across this chaotic land, bold and tenacious men launched the first railway in Central Africa." |

![Expat [DESTINATIONCOMPLETE]](http://www.expat.com/logo/expatBlogSmall.gif)